This op-ed was published in shorter form online on June 26, 2021 by the Toronto Star, on June 27, 2021 by the Vancouver Sun and on June 28, 2021 by the Huffington Post.

As Canada turns 146, many recent surveys show that most Canadians are hankering for a new constitution.

In 1992, more than 14.5 million Canadians did something they had never done before – they voted in a referendum on changes to Canada’s Constitution as proposed in the Charlottetown Accord. While that set of changes was rejected by a majority, many of the issues continued to simmer leading up to the 1995 referendum proposing the separation of Quebec, narrowly won by the No side.

Ongoing negotiations led to some of the Charlottetown Accord changes being implemented, along with many of 1987 Meech Lake Accord changes, through bilateral agreements between the federal and provincial governments (especially Quebec).

Ongoing negotiations led to some of the Charlottetown Accord changes being implemented, along with many of 1987 Meech Lake Accord changes, through bilateral agreements between the federal and provincial governments (especially Quebec).

So is Canada’s Constitution a completed document? Some commentators have claimed since 1995 that Canadians are tired of constitutional talks, and while this was likely true back then there is no evidence that the fatigue continues.

In fact, of the total population of about 34 million Canadians, about 9 million are age 15-34, and they have never taken part in a public discussion of Canada’s Constitution as they were not old enough to have voted in the 1990s referendums. Another 5 million people have immigrated to Canada in the past 20 years. As a result, about 14 million Canadians (41% of the total population) have never been asked by governments about what they think of Canada’s Constitution.

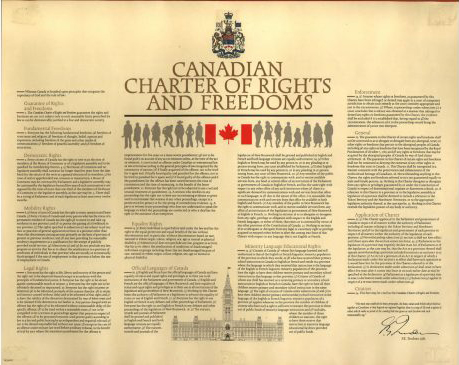

Surveys show that a large majority of Canadians support the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, and a study last year concluded that the Charter was the most influential individual constitutional rights document in the world.

However, recent surveys also show that a majority of Canadians want other key parts of our Constitution changed, specifically to make our governments more democratic and accountable.

A February 2013 survey found a majority of Canadians (55%) want to change to a democratically chosen Canadian Head of State, while only 34% want to continue with a member of the British royal family as Canada’s Head of State.

Given they are appointed and represent the monarchy as Head of State in Canada, many commentators have pointed out that the Governor General and the provincial lieutenant governors lack the democratic legitimacy to stop the Prime Minister or premiers from abusing their powers.

Concerns about these powers have likely increased over the past decade as the Prime Minister and premiers have called snap elections or shut down legislatures at times that suit them or their political party, and as elections have produced minority governments and situations raising serious questions about who has a right to govern, how a government can be defeated in the legislature, and whether an election should happen.

A December 2012 survey found that 84% of Canadians want restrictions on key powers of the Prime Minister and provincial premiers with clear written rules that can be enforced, and a May 2012 survey showed that 67% of Canadian want a new, elected person to replace the Governor General and lieutenant governors who will have the democratic mandate to say no to the PM and premiers.

Most countries in the world have restrictions on the powers of their leaders written in their constitution, and even Britain, Australia and New Zealand have at least written down these constitutional conventions. And most have a democratically chosen head of state.

As well, a May 2013 survey found 71% of Canadians want legal restrictions on party leader powers to give more freedom and power to politicians in each party.

Other recent surveys have shown more than 70% of Canadians want the Senate reformed or abolished, and that a majority support changes so that Quebec will ratify Canada’s Constitution as the federal government and other provinces did in 1982.

Other controversial ongoing constitutional issues include Cabinet appointment powers (especially for appointing judges), Canada’s voting system, Aboriginal self-government rights, and the division of powers between the federal, provincial and territorial governments.

The Charlottetown Accord development process and referendum, and previous processes, show that making a new Canadian Constitution is not at all easy. However, ignoring key issues and changes that a majority of Canadians want is also not a democratic solution.

As Canada moves toward its 150th birthday in 2017, what more appropriate national discussion could take place than about the document that founded both our country and our governments, and about the changes Canadians want in a new constitution?

Should a new Canadian Constitution make key changes in the areas mentioned above? You can see key info and send a letter letting key politicians across Canada know what you think HERE.